Predicting feedback perception in an online language learning task using EEG and machine learning

By Dylan Scott Low Y.J., & Stephanie Fu Pei-Yun

Published on June 10, 2023

June 10, 2023

Project definition

Background

In recent years, new apps and products have been introduced based on the idea that machine learning techniques could be applied to EEG brainwaves in order to decipher a person’s thoughts and generate statistics about the different kinds of thoughts a person has in a day (e.g, Neurosity; see also Houser, 2019; Fireship, 2023). Our motivation is to attempt to implement our own simple machine learning analysis on raw EEG data to discern cognitive activity, especially that related to language. We selected a dataset containing EEG data recorded while participants completed language learning tasks in the online platform, Duolingo (see “Data” below). Our main objectives in this project were to develop a pipeline for analysing EEG data (OpenBCI format) using open source tools like MNE Python and apply machine learning methods to the analysis. Our personal learning objectives were to make ourselves more familiar with EEG data analysis, the Python programming language and corresponding workflows, and other open source tools used in neurosciencce research.

The main question we asked in this project was: How can we use machine learning techniques to identify, based on EEG data, if the participant was receiving positive feedback (they got the learning task correct) or negative feedback (they got the learning task wrong) from Duolingo?

Tools

The project relied on the following tools:

- R programming language (packages: tidyverse, ggplot2, readr)

- Python programming language (libraries: pandas, scikit-learn, MNE Python)

- Git/GitHub

- Bash terminal

Data

The data we used comes from a project titled Data in Brief: Multimodal Duolingo Bio-Signal Dataset by Notaro & Diamond (2018; click here for the corresponding article). As suggested by the title, this is a multimodal dataset. Four kinds of data were recorded: (1) EEG via a low-cost OpenBCI electrode cap, (2) Gazepoint-GP3 eye-tracking, (3) Autohotkey cursor movements and clicks, and (4) Autohotkey screen content data (screenshots taken when a click occurs). Data was recorded while participants (n = 22) were completing beginner German language lessons on the desktop version of Duolingo. Participants were either English native speakers or fluent in English.

Our project focused on (1) and (4), that is, the EEG and screenshot data. In particular, we analyse only the data of participant 1.

Deliverables

At the end of this project, these files will be available:

- A .txt file (data_labels_raw.txt) containing manually selected filenames (timestamps) of the screenshots corresponding to when the participant receives feedback on their Duolingo performance.

- An R script (data_labels.r) for cleaning the raw filenames list (data_labels_raw.txt) into machine-readable format (data_labels_clean.txt).

- A Jupyter notebook containing Python script for preprocessing the OpenBCI EEG data (high and low pass filtering).

- An R script (data_labelling.r) for combining the filtered EEG data with the data_labels_clean.txt file.

- A Juyter notebook containing Python script for running machine learning classifiers (e.g., MLP, kNN, random forest) on the labelled EEG data.

Results

Progress overview

At first, we thought preprocessing the data would be a simple matter. However, we quickly realised that the OpenBCI EEG format (formatted as a .txt file) is not a standard raw EEG format that could be easily imported in MNE Python. Solving this problem caused us some delays, but we eventually came up with a custom script to import the data in MNE Python. Another peculiarity we observed was that the OpenBCI set-up only consisted of 8 electrodes, as opposed to the standard 32 channels.

Also, we initially intended to analyse the data of more than one participant in the data set, but realised that even data from one participant (recorded over about 58 minutes) was very large, and likely more than sufficient to train an ML model. The large size also delayed our work due to the long wait times when processing the data, sometimes leading to crashes which force us to start the process over again until it reaches fruition (an unfortunate symptom of running such analyses on weak personal machines).

Tools we learnt during this project

- MNE Python: We learnt how to filter raw EEG data during the preprocessing stage, as well as how to import EEG data even if not in a recognised standard raw format.

- Github workflow: We got well-acquainted with using Git via the Bash terminal, and also some related tools like Datalad and Git LFS (Large File System).

- Bash Terminal: We gained a good understanding of how to use the Bast erminal in lieu of File Explorer (Windows)/Finder (Mac).

Results

Figures and Plots

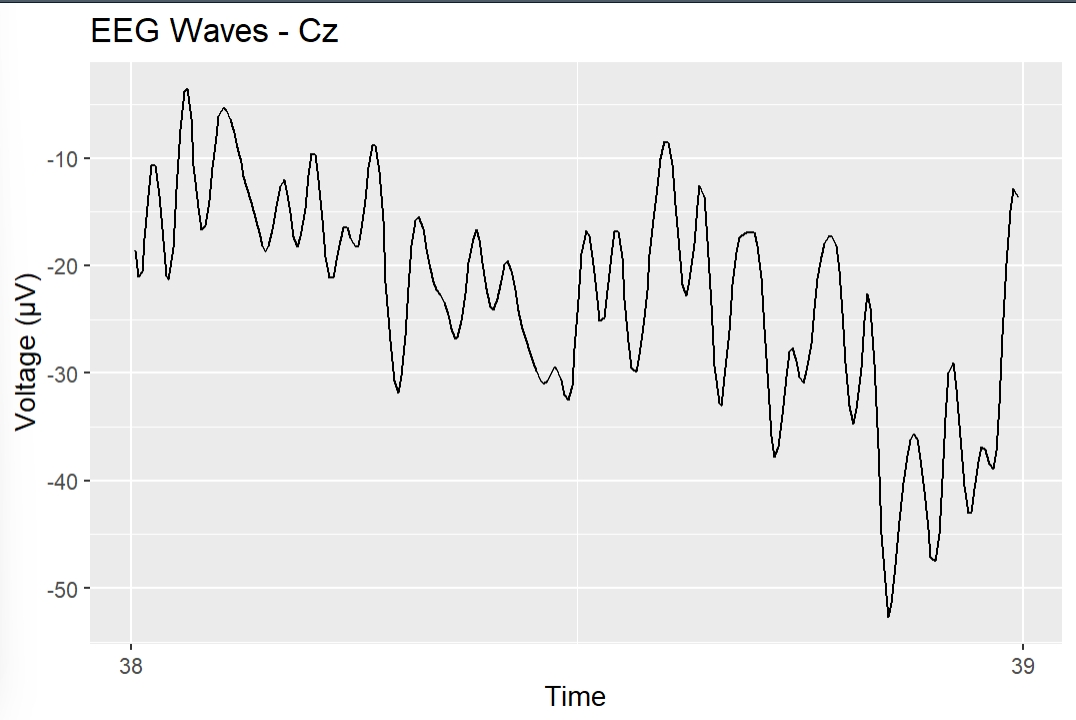

Preprocessing

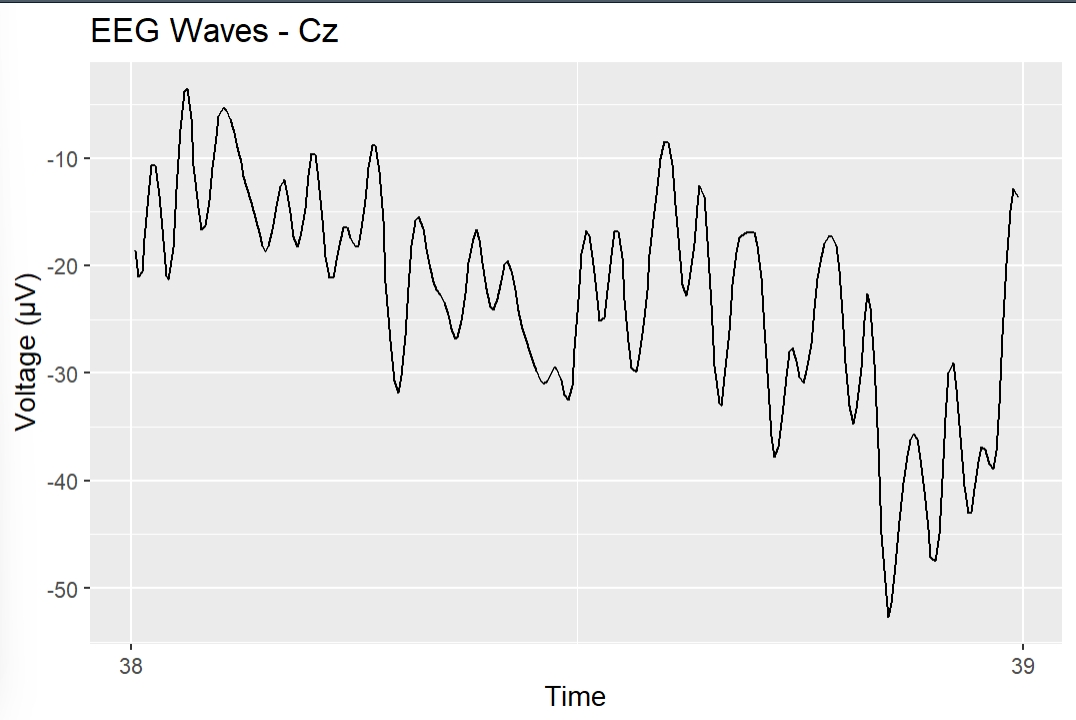

Unfiltered Cz Channel during 1 second epoch.

Unfiltered Cz Channel during 1 second epoch.

Filtered Cz Channel during 1 second epoch.

Filtered Cz Channel during 1 second epoch.

Unfiltered F3 Channel during 1 second epoch.

Unfiltered F3 Channel during 1 second epoch.

Filtered F3 Channel during 1 second epoch.

Filtered F3 Channel during 1 second epoch.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) plot for the unfiltered EEG.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) plot for the unfiltered EEG.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) plot for the filtered EEG.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) plot for the filtered EEG.

EEG cap sensor positions.

EEG cap sensor positions.

Machine Learning

Feature Importance (Random Foreest)

Feature Importance (Random Foreest)

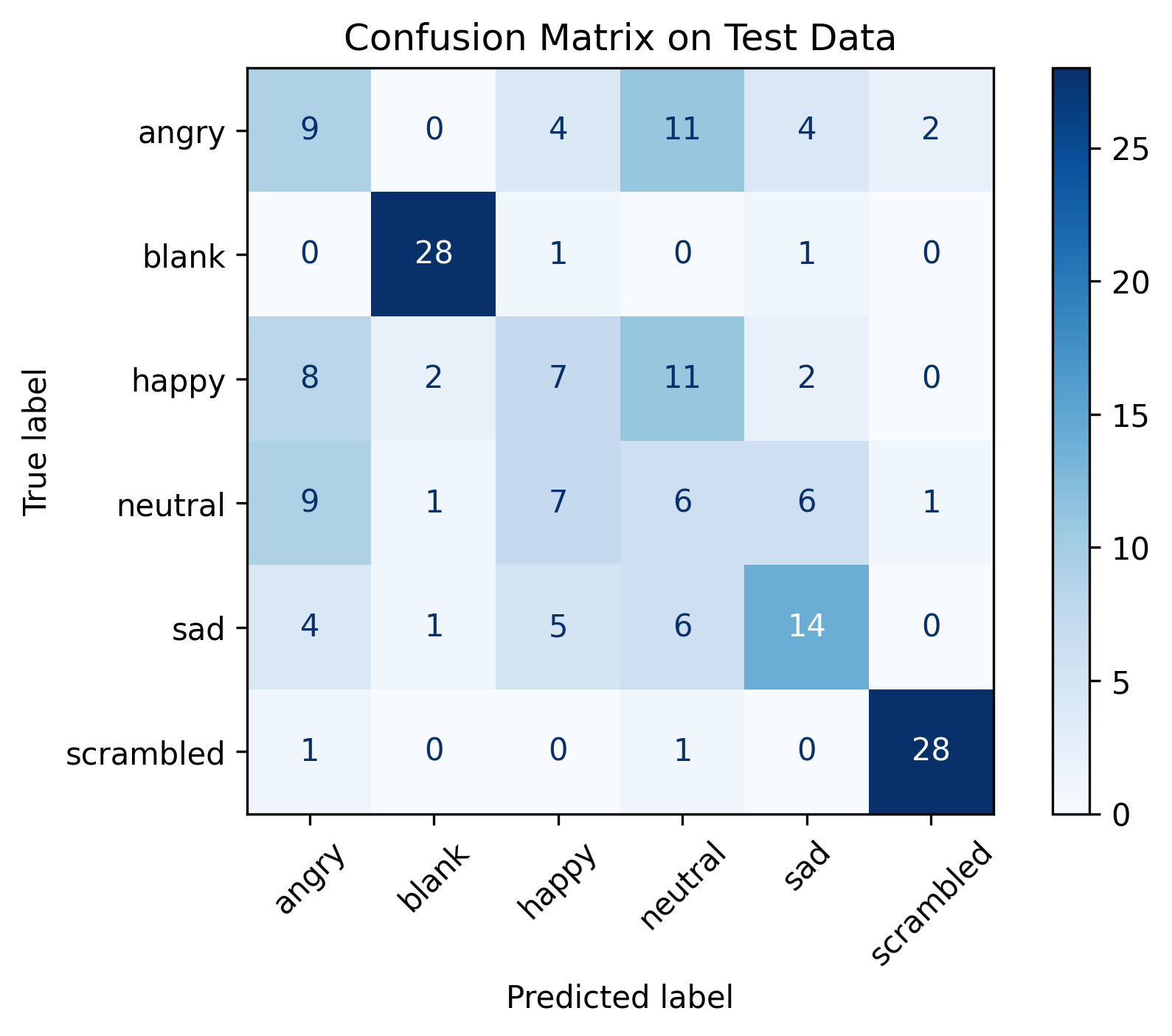

Confusion Matrix (Random Forest)

Confusion Matrix (Random Forest)

Feature Importance (kNN)

Feature Importance (kNN)

Confusion Matrix (kNN)

Confusion Matrix (kNN)

Feature Importance (Logit)

Feature Importance (Logit)

Confusion Matrix (Logit)

Confusion Matrix (Logit)

Feature Importance (Multilayer Perceptron)

Feature Importance (Multilayer Perceptron)

Confusion Matrix (Multilayer Perceptron)

Confusion Matrix (Multilayer Perceptron)

Discussion

The full results can be viewed in the Jupyter notebook ml_eeg_classifier in our GitHub repository. We briefly summarise the accuracy rates attained by each model below.

Random Forest: 0.8923478119142694

Logistic Regression: 0.5955504848830576

k-Nearest Neighbours: 0.9759595794963736

Multilayer Perceptron: 0.6984760818189226

A prima facie look will show that the k-Nearest Neighbours (kNN) classifier achieved the highest performance in accurately predicting whether the participant was looking at positive or negative feedback based on the EEG data. However, it is possible that the high accuracy rate may be due to overfitting, and more sophisticated evaluation metrics will need to be consulted (unfortunately, time limits prevent us from doing so here).

Future directions for this project could involve exploring more advanced machine learning techniques, such as deep learning models, to capture complex patterns in the EEG data. Additionally, incorporating other modalities available in the multimodal dataset, such as eye-tracking or cursor movements, could potentially enhance the prediction accuracy and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the cognitive processes during language learning.

Conclusion and acknowledgement

In summary, this project provides a starting point for applying machine learning methods to EEG data analysis in the context of language learning. The results highlight the potential of using EEG features to predict certain cognitive tasks, but further research is required to refine this (admittedly) very coarse implementation and address the aforementioned limitations.

We humbly thank the Brainhack School Team for organising this fantastic learning journey, as well as all the instructors who developed the learning modules and corresponding video lectures/lessons. We would especially like to thank the Taiwan Hub team (National Taiwan University and National Central University) for all their support and encouragement.