fMRI Signatures and Behavioural Correlates of Self and Empathic Pain

By Lyanne Zhang, Onjoli Krywiak, Leen Ghanayem, Clarize Donato, Kayla Teopiz, & Quin Xie

Published on June 13, 2025

June 13, 2025

Project definition

Background

Empathy is conceptualized as an individual’s ability to perceive, understand and respond appropriately to someone else’s experience.1,2 In addition, empathic pain is commonly defined as an individual’s perception and emotional response to another person’s suffering or painful situation.2 The cognitive component of empathy and empathic pain includes perspective taking and maintaining distinction between the self and others.3 Taken together, it is proposed that disparate neural mechanisms subserve the cognitive processes that comprise empathy and empathic pain.3,4

Meta-analytic neuroimaging data suggest that multiple brain regions are implicated in empathic pain, including but not limited to the insula cortex (IC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), mid-cingulate cortex (MCC), and nucleus accumbens (NAc).3,5 It is postulated that the IC and ACC are critical regions of interest (ROI) in the processing of emotional states and motivation.6 In addition, it has been observed that functional connectivity between the MCC and IC is increased during pain perception in others.7 Furthermore, the NAc has been implicated in the prediction of empathic-pain related behaviours (e.g., actions to help an individual in pain).8 However, the underlying neural circuitry and networks that subserve empathic pain remain insufficiently characterized. Moreover, it is not known how sociodemographic, clinical and/or behavioural factors (e.g., loneliness or social connectedness) may mediate or moderate neural mechanisms that subserve empathic pain.

Herein, this project aimed to apply analytical methods using Python to investigate neural activation and functional connectivity in the IC, ACC and related brain regions in adults completing an fMRI and empathic pain task paradigm.

Main Objectives

- Produce a neuroimaging workflow for task activation analyses, functional connectivity analyses, and data visualization.

- Produce a GitHub Repository to enable reproducibility of our analyses.

Tools

- Software

- Python packages: Nilearn Library

- MS Visual Studio Code

- R and RStudio

- Code and Project Management

- Git and GitHub

- Scripts

- Jupyter Notebook

- Computing Environment

- Local Laptops

Data

This project investigated an Open Source dataset obtained from OpenNeuro [https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds006243/versions/1.0.3]. The dataset consists of fMRI data collected from 54 participants trained in one of two meditation modalities: Loving Kindness Meditation (LKM) (n = 25) and Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) (n = 29). The empathic pain task paradigm consisted of two counterbalanced runs, Experience (Self) and Observe (Other) conditions, each containing 30 trials that were 24 seconds in duration, with a total of 720 seconds for a single run. Each run (i.e., 30 trials) included 15 trials involving anticipation of fear and 15 trials involving pain experience. An audio cue was used to indicate whether the participant or study partner would receive a pressure pain stimulus. The pressure pain stimulus was transmitted through a tube to a piston secured on the participant’s thumbnail.

All participants completed the empathic pain task during an fMRI scan in order to examine neural responses to self-pain test condition (i.e., pain stimulus of the participant’s hand) and empathic pain (i.e., observing someone else receive the pain stimulus). MRI data was collected at the Center for Functional and Molecular Imaging at Georgetown University using a 3T Siemens TIM Trio scanner. High-resolution structural images were acquired using a T1-weighted MP-RAGE sequence (1 mm isotropic voxels), and functional images were collected using a T2*-weighted EPI sequence (3 mm isotropic voxels, TR = 2,500 ms, TE = 30 ms).

Deliverables

Methods

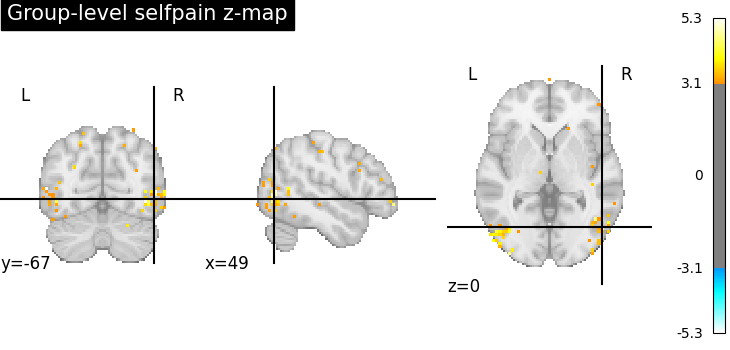

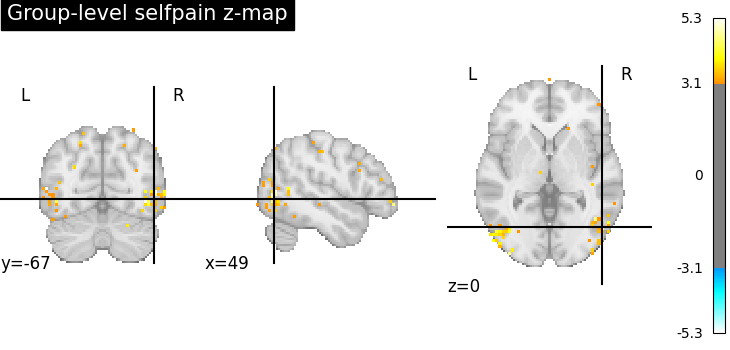

Task Activation Analysis

To examine brain regions activated during the empathic pain task, fMRI data was fitted to a first-level general linear model using Nilearn’s FirstLevelModel to compute z-maps for each task contrast. A statistical threshold (z > 3.1) was applied, and significant clusters were identified and labeled using Nilearn’s get_cluster_table and the Harvard-Oxford atlas, respectively. Further, a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to examine whether baseline loneliness and social connectedness scores predicted activation of brain regions implicated in empathic and self-experienced pain, specifically the ACC, IC and superior temporal gyrus, following the meditation intervention. The UCLA Loneliness Scale9 and Social Connectedness Scale10 were used to measure loneliness and social connectedness at baseline.

Functional Connectivity Analysis

We aimed to compare functional connectivity between self-experienced and empathic pain conditions. First, we applied the masker to all files using the Harvard-Oxford brain atlas, which provides good parcellation of subcortical regions. Next, we generated one connectivity matrix (based on Pearson’s correlation) per condition for each subject. We then computed a network-blocked mean connectivity matrix for each condition for visualization purposes. To compare connectivity between the two conditions at the edge level, we performed paired t-tests with FDR correction.

We were also interested in investigating whether functional connectivity is associated with loneliness or social connectedness. To investigate this possible association, we used our participants’ previously obtained individual functional connectivity matrices, where each participant had two matrices: one for run 1 (self) and run 2 (other/empathic pain). Then, we categorized participants’ functional connectivity matrices by run type (i.e., 1 vs 2). As well, we were interested in only functional connectivity/roi-to-roi pairs that had either the insula/insular cortex or the cingulate cortex/gyrus as one of the rois in a pair.

Finally, to test potential associations between functional connectivity with loneliness or social connectedness, statistical analyses were performed via linear regression models. Functional connectivity of specific roi pairs (i.e., those containing insula or cingulate cortex), and covariates including age, sex, and condition were included as predictors, while our dependent/predicted variables included loneliness or social connectedness.

Partial Least Square - Covariance (PLS-C) Analysis

To examine changes in functional connectivity between the two conditions in an unsupervised manner, we performed PLS-C analysis on the correlation matrix between all 69 parcellated regions.

Results

Task Activation Analysis

Finding #1: Many regions are activated during self pain and empathic pain tasks

Various cortical and subcortical regions were activated during the self-pain and empathic-pain tasks, including brain regions in the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes. The empathic-pain condition was characterized by decreased activation of the frontal medial cortex and increased activation of the posterior division of the inferior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus and temporal fusiform gyrus. On the other hand, the self-pain condition was characterized by decreased activation of the cuneal cortex, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and increased activation of the supracalcarine cortex.

Figure 1. Heatmap displaying activation by region for self and empathic pain tasks.

Finding #2: Interaction between baseline loneliness and condition predicts activation in the ACC during self pain task

Upon examining whether baseline loneliness and social connectedness predicted brain activation during the empathic and self-pain tasks, a MANOVA revealed a significant interaction between baseline loneliness and activation of the ACC in the self-pain condition (p = .03). Specifically, participants in the LKM meditation group showed a significant decrease in ACC activation at higher baseline loneliness scores. There was no signficant interaction between

Figure 2. Interaction plot visualizing the relationship between baseline loneliness scores and activation in the ACC during self pain task.

Functional Connectivity Analysis

Finding #1: No difference in functional connectivity between self and empathic pain tasks

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not observe any statistically significant differences in connectivity between the self and empathic pain conditions at the edge level, even before correcting for multiple comparisons.

Figure 3. Functional connectivity matrices for self pain (left) and empathic pain (right) tasks.

Finding #2: Functional connections are associated with social connectedness but not loneliness

Several functional connectivity pairs containing our rois of interest (cingulate cortex and/or insula) were negatively associated with social connectedness in both self and empathic pain tasks. Notably, these significant associations do not pass FDR correction. In contrast, our functional connectivity pairs of interest were not significantly associated with loneliness. It appears that our rois of interest, these being the cingulate cortex and/or insula, that are typically implicated in empathic pain tasks, are also functionally connected with other regions of interest and are associated with social connectedness. This highlights that functional connectivity with our rois of interest that underlie empathic pain also appears to underlie behaviour such as social connectedness.

Figure 4. Significant functional connections between roi pairs of interest and self pain (left) and empathic pain (right) tasks.

PLS-C Analysis

The first two PLS components captured the majority of the covariance between neural connectivity (Figure 5). There did not seem to be significant differences between participants in the LKM group and those in the PMR group in the first two PLS components, consistent with previous functional connectivity analyses. However, the timing of fMRI collection (before or after the task) seemed to be the major contributor to the separation on the first PLS component (Figure 6). Using a correlation test, we examined whether either PLS component was associated with loneliness or social connectedness and found no significant correlation. These findings suggest that while the two interventions might have changed functional connectivities, they did not significantly affect loneliness or trait empathy of the participants.

Figure 5. Explained variance in functional connectivity by the top 5 PLS components.

Figure 6. Projection of functional connectivity onto the first two PLS components.

Conclusion

- The results of our analyses support that activation in the ACC and IC was higher in the self-experienced pain condition compared to the empathic pain condition.

- In the LKM group, higher loneliness was associated with lower ACC activation. This effect was not observed in the PMR group.

- Functional connectivity did not significantly differ between self-experienced pain and empathic pain conditions.

- Functional connectivity in ROI pairs of interest (cingulate cortex and insula) was associated with social connectedness in both self and empathic runs, but these associations did not survive FDR correction.

Acknowledgements

Thank you Brain Hack School 2025 team for all the help!

References

- Decety J, Smith KE, Norman GJ. Halpern A social neuroscience perspective on clinical empathy. J Halpern A social neuroscience perspective on clinical empathy World Psychiatr 2014;13:233–7.

- Cao Y, Zhang J, He X, et al. Empathic pain: Exploring the multidimensional impacts of biological and social aspects in pain. Neuropharmacology 2024;258(110091):110091.

- Jauniaux J, Khatibi A, Rainville P, Jackson PL. A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on pain empathy: investigating the role of visual information and observers’ perspective. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2019;14(8):789–813.

- Tremblay MPB, Meugnot A, Jackson PL. The neural signature of empathy for physical pain … not quite there yet! In: Social and Interpersonal Dynamics in Pain. Cham: Springer; 2018.

- Zhang M-M, Chen T. Empathic pain: Underlying neural mechanism. Neuroscientist 2025;31(3):296–307.

- Zhang M, Wu YE, Jiang M, Hong W. Cortical regulation of helping behaviour towards others in pain. Nature 2024;626(7997):136–44.

- Zaki J, Wager TD, Singer T, Keysers C, Gazzola V. The anatomy of suffering: Understanding the relationship between nociceptive and empathic pain. Trends Cogn Sci 2016;20(4):249–59.

- Hein G, Silani G, Preuschoff K, Batson CD, Singer T. Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members’ suffering predict individual differences in costly helping. Neuron 2010;68(1):149–60.

- Russell, D , Peplau, L. A.. & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42, 290-294.

- Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310